For Miss A. Lee, my teacher 1962-1964

Prologue

Because I live in Australia, I do not have access to the material in archives and libraries in England which is necessary in order to write a complete history. For that reason, I can only claim to have written notes towards a history, based entirely upon, and limited by, what is available to me here in Australia and on the internet. I owe a debt of gratitude to Google Books, and to the State Library of Victoria, especially its online service. Without these resources I could not even have attempted this small task.

Miss Lee, to whom this work is dedicated was a wonderful teacher, who was very special to me. I feel both fortunate and privileged to have been in her class for two whole years—my two final years at Victory Primary School.

Prehistory

The sequence of events that would lead to the founding of a new school at Victory Place in 1874 can be said to have begun with the passing of the Elementary Education Act in August 1870.[1]

The Act, which demonstrated for the first time a government commitment to the provision of elementary education nationally, required that elected school boards be formed in the boroughs or parishes in which they were needed. These would be responsible for the building and administration of “board schools”.

In the case of London, a School Board for the whole metropolitan area was created with the election of members being held in November and the first Board meeting taking place on 15 December 1870.

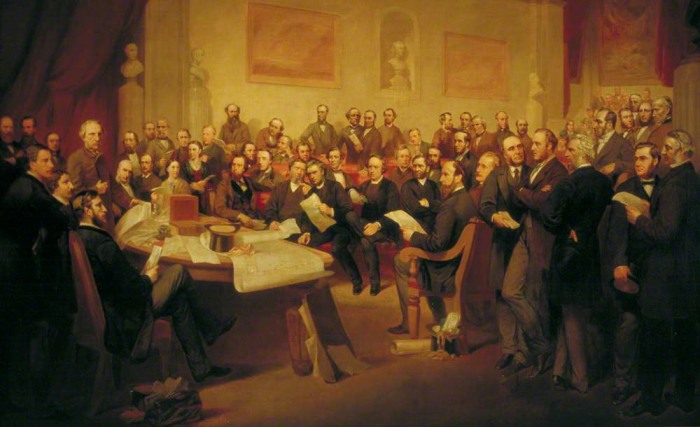

“The First London School Board” by John Whitehead Walton

The School Board for London quickly set to work on one of the most urgent tasks facing it—the erection of school buildings in areas where not enough school places were available:

At a very early period of their existence the Board... decided to apply to the Education Department for authority to provide forthwith a limited number of schools in the districts where the deficiency of school places had been ascertained to be very great.

The Statistical Committee were instructed to select the localities for these schools; and after consultation with the Divisional Members, application was made to the Education Department for power to establish twenty schools in London, located as follows: One in Chelsea, three in Finsbury, one in Greenwich, two in Hackney, one in Lambeth, four in Marylebone, three in Southwark, four in Tower Hamlets, and one in Westminster.

The application was made to the Education Department on July 6th, 1871, and so impressed were the Department with the urgent need for school provision, that they sanctioned the erection of these twenty schools on July 11th.[2]

Victory Place School was not one of this first batch of schools, of which three were in Southwark, but it was one of the first ninety nine schools provided by the Board, which in the thirty three years of its existence constructed more than four hundred new schools! [3] In fact, according to the Board representatives at the school’s opening ceremony, it was the 70th school opened by the Board. [4]

Locks Fields

By 1872 the School Board for London had decided that a new school was necessary in the area known as Locks Fields, and was considering two locations for it, Victory Place and Salisbury Crescent.

Locks Fields was a reclaimed swamp which was fast being built up.

Since the commencement of the present century a considerable advance has been made in the way of buildings in this neighbourhood, particularly on the east side of the Walworth Road. Lock's Fields, formerly a dreary swamp, and Walworth Common, which was at one time an open field, have been covered with houses.[5]

Lock or Locks Fields were so called because of a leper hospital—the Lock Hospital—which used to be situated by the Neckinger River where Bartholomew Street meets Great Dover Street.[6] The origin of the word “lock” as used here is uncertain. It could be from the old French loques meaning rags, i.e., the rags applied to leprous sores, or it could be from the Saxon loq, to be closed in. Whatever its origins, the word “lock” came to mean, inter alia, “an infirmary”, and is so defined in Nathan Bailey's dictionary of 1721.[7]

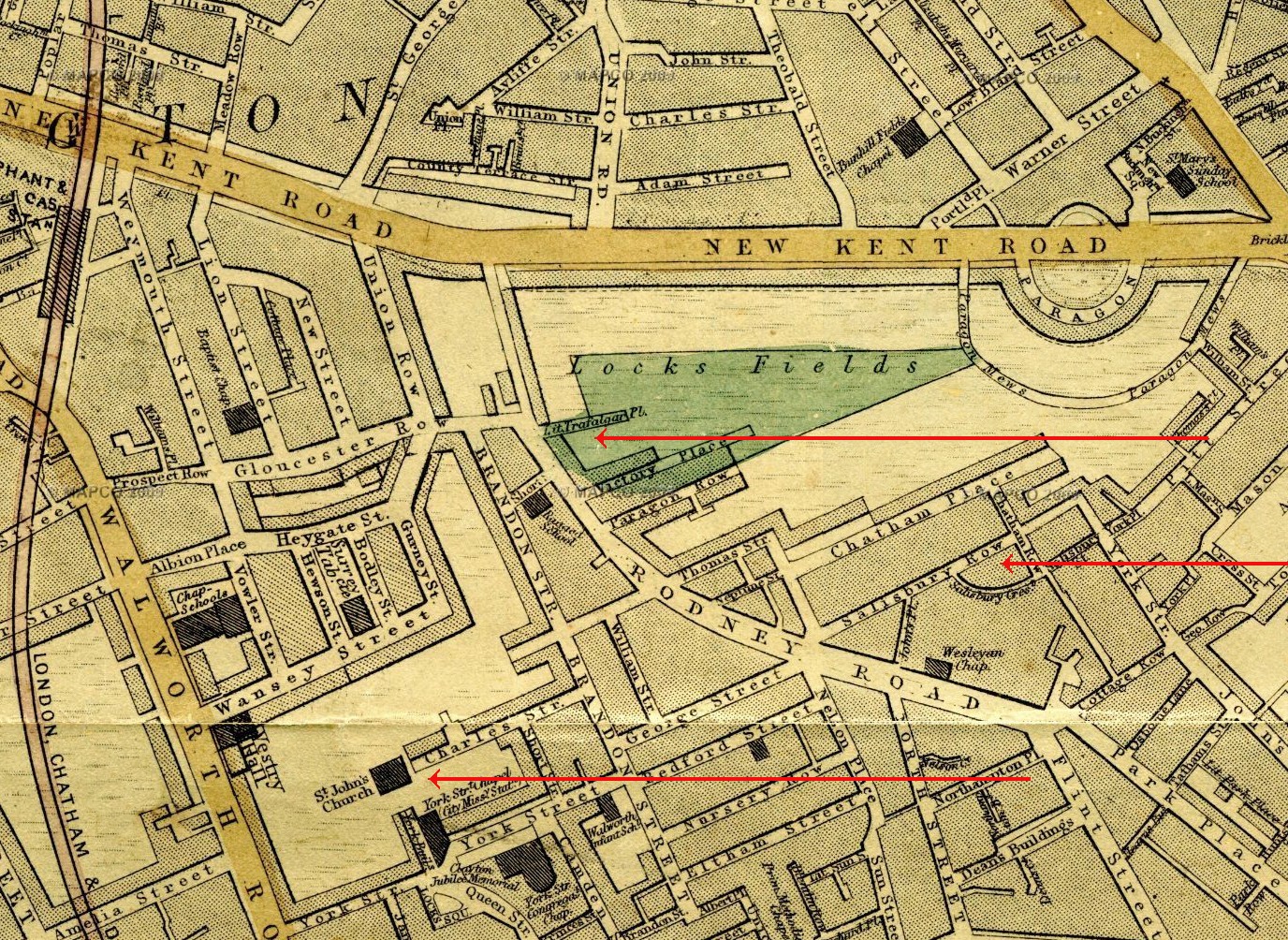

The Weller London map of 1868 (detail above) shows that, East of Rodney Road, Locks Fields were still mostly open ground in the late 1860s.[8]

The two upper red arrows point to the two locations being considered for the new school, Victory Place and Salisbury Crescent. The lower arrow points to St. John’s Church which is mentioned in the text below.

The Nearby Ragged School

It is interesting to note that according to the map above, there was a Ragged School on the other side of Rodney Road, right by the site for the new Victory Place School. [9]

However there is no mention of this ragged school in the Minutes of the School Board’s meetings in 1873—the year in which the establishment of the Victory Place school was being planned. [10]

What we do find therein is a controversy stemming from the proximity of St. John’s National School. This was founded in 1866 by St. John’s Church, and was perhaps too new to have been included on the map above. [11]

It is not possible to be certain without further evidence, but I surmise that by 1872 the ragged school was no longer in existence, otherwise it would surely have been mentioned in the Boards deliberations. Perhaps it closed down as a consequence of the creation of the new National School of St John’s.

[GENERAL NOTE: In 1811, an Anglican society was established “for Promoting the Education of the Poor in the Principles of the Established Church in England and Wales”. Schools founded by this National Society were called “National Schools”.]

Opposition from St. John’s

When it became known that the School Board was planning to build a new school in the Locks Fields area, the managing committee of St. John’s School sent a memorial to the Board, dated 23 December 1872, objecting to this initiative. [12]

The memorial was referred by the School Board to its Statistical Committee “for consideration and report”, and at the next Board meeting the following response from that Committee was tabled:

The Board on the 8th instant referred to the Statistical Committee a Memorial from the Managers of the St. John's, Walworth, National Schools, objecting to the erection of a Board School upon either the Victory-place or the Salisbury-crescent Sites. These Sites were alternative ones, and of the two the Site in Victory-place has been selected for the erection of a School for 1,000 children. The site in Victory-place is slightly to the south of the New Kent-road, and a third of a mile to the north-east of the St. John's Schools. It falls in Sub-Division Q. one of a group of four Sub-Divisions (O Q R S) where there is a total deficiency of 2,369, and where the Education Department have sanctioned the proposal of the Board to provide School places, in all, for 2,000 children. The Committee have considered the statements made by the Memorialists, and also the statistics quoted by them, which, however, are confined to the ecclesiastical parish of St. John's, Walworth. They find that all the existing and projected Schools, enumerated by the Memorialists, have already been taken into account by the Board for the full amount of accommodation which they will provide. The supposition that the inhabitants of all houses rated at more than £20 may be disregarded, the Committee consider as decidedly erroneous. After careful deliberation, and having ascertained that the amount of efficient School accommodation in the locality has decreased since the publication of the Report to the Education Department, the Committee recommend that a reply be sent to the Memorialists, informing them that the Board are of opinion that no valid objection has been made to the erection of a School upon the Victory-place site. [13]

The rejected memorial was followed by two letters in succession from the Rev. G. T. Cotham of St. John’s “urging further reasons against the erection of the proposed Board School in Victory-place”. Both documents were referred to the Statistical Committee, and the arguments of both were rejected. [14]

In their response to the Rev. Cotham’s second letter, the Committee stated that he had

...considerably under-estimated the number of children requiring elementary education in his district, which is amongst the poorest on the south side of the river... After careful consideration the Committee are of opinion that the proposed Board School upon the Victory-place Site is needed, and that however valuable Mr. Cotham's Schools may be, they do not supply the entire educational wants of the surrounding neighbourhood. The Committee accordingly recommend that a reply be forwarded to Mr. Cotham, to the above effect. [15]

The Site

In the meantime, a decision had been made to build the new school on the Victory Place site. This decision was taken at the Board Meeting of 29th of January 1873, where it was decided to proceed with the purchase of the site. All told there were 15 houses on the site at the time, which would have to be bought and demolished: seven in Little Trafalgar Place, four in Victory Place, and four in Rodney Road. [16]

However the map above shows buildings only along the Rodney Road and Victory Place boundaries of the site for the new school. No buildings are shown on the school site’s northern boundary Little Trafalgar Place, later renamed Elba Place. Presumably then, the seven houses in Little Trafalgar Place were newly built.

The Opening Ceremony

At the Board Meeting of 30th of July 1873 the Works Committee reported that tenders had been invited for the erection of a School to accommodate 1,024 children, on the site in Victory Place, and accepted the tender of the builders Cooke and Green, of Marlborough-street, Blackfriars, for a cost of £8440. [17]

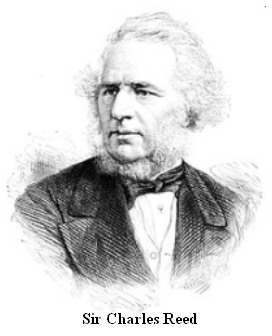

The building work proceeded quickly, and by November 1874 the new school was ready. The opening ceremony took place on Tuesday 24th of November, presided over by Sir Charles Reed and the Vice-Chairman of the School Board Mr. Edmund Hay Currie. The Times reported on the following day as follows:

From statements made by Sir Charles Reed and Mr. Currie, it appeared that after taking into account all the accommodation afforded by existing efficient voluntary schools, there was a deficiency of accommodation to the extent of 2,009 places. The School Board for London was created for the purpose of supplying such a want as this, and not, as had been said so often of late, to establish schools in opposition to any efficient schools already in existence. Instead of wishing parents to take their children from any existing voluntary school found to be efficient, the Board earnestly hoped that parents would not remove their children from such. [18]

Clearly the spectre of the Rev. Cotham hung over the proceedings, and the Board’s speakers are keen to show goodwill towards existing local schools.

It is likely in fact that the Rev. Cotham was there in person. After the rejection of his objections to the new school, he seems to have decided that “if you can’t stop them, you must join them”, and got himself appointed as one of the eight Managers of the new school. [19]

It is a reflection of his influence in the area that a road still bears his name. It lies only a little distance from the Church he built and the school he founded.

The Times report continues with a rather surprising statement, given that this was before motor cars, about traffic safety and the modest positioning of the new schools.

As in the case of all the other schools erected by the Board, care had been taken that the site of the school should be in such a position that there would be no danger of the children being run over in coming or going from school. This accounted for their schools being in by-streets, instead of being shown off to greater advantage in our public thoroughfares.

The Original Buildings

The character of the new schools built by the School Board for London owed much to the ideas of the architect Edward Robert Robson, who was appointed chief architect for the London School Board in 1871.[20] It was Robson himself who designed the buildings for the Victory Place Board School. We can get a fairly detailed picture of what they were like from a description in the trade periodical The Architect:

These schools are situated at the corner of Rodney Road and Victory Place, near the Elephant and Castle. They consist of two separate buildings, one for infants, of one storey in height, and the other, of three storeys, for the boys and girls, the latter being placed on the first and the former on the second floor, the ground-floor being entirely open (except the caretaker’s apartments, & c.), and forming an extensive covered playground for the girls and infants. Each school contains a large school-room with four class-rooms adjoining, the infants’ having, in addition, extensive class-rooms for the use of the “babies.” Each department has separate access, with ample lavatory and cloak-room contiguous. Especial attention has been paid throughout to the sanitary arrangements, and the playgrounds are exceptionally large and commodious. In the elevation Portland stone bands have been introduced to relieve the stock brick facing and the red brick dressings. The school will accommodate nearly 1,000 children, and has been erected by Messrs. Cook & Green, contractors, from the designs of Mr. E. R. Robson, Mr. R. Walker acting as clerk of works. The amount of the contract was under 8,500/.[21]

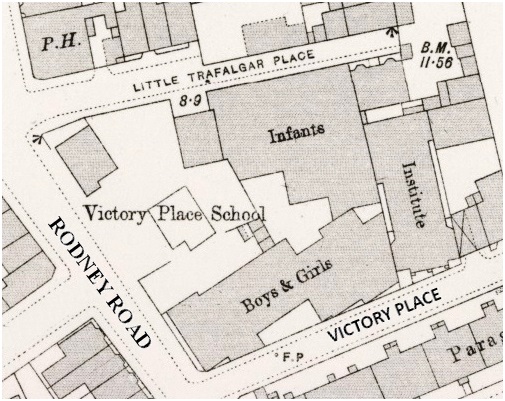

In addition the Ordinance Survey Map of London published in 1895 gives a very clear idea of how the buildings were situated on the site and in relation to each other:[22]

The layout of the school buildings in 1893

I have only been able to find one photograph of the original school buildings. This seems to be a view of the main building from Rodney Road, taken from roughly where the “Y” of “RODNEY” is on the Ordinance Survey Map above.

The original school building

As can be seen in the photograph, the 1875 school buildings were sombre and somewhat Gothic in style. At three storeys high the main building formed an impressive and perhaps intimidating structure in relation to its surroundings. This was probably intentional.

Charlie Chaplin (1889-1977)

It was in the original buildings, some twenty years later, that Charlie Chaplin got his first taste of schooling. His teacher Mrs E. E. Turner-Dauncey recalled that she taught Charlie Chaplin at Victory Place Board School when he was between four and five.

“I remember his large eyes, his mass of dark curly hair, and his beautiful small hands. He was very sweet and so shy. He copied his famous walk from an old man who gave oatmeal and water to the horses with cabs and carts outside the Elephant & Castle.”[23]

Mr W. H. Libby, Headmaster in the Late 1890s

William Henry Libby seems to have been an exceptional headmaster. He is referred to in an article in the The Manchester Guardian Weekly as one of those caring teachers who cultivate an enduring relationship with their pupils:

... Well, children need love. Sometimes they find it in the master or mistress at the day school. Oh, yes, indeed. I had not known Walworth many weeks before I met lads and young men to whom the title “One of Mr. Libby's boys” (Mr. Libby, head master of Victory Place board school in the late [eighteen] nineties) was a source of pride... [24]

However he is primarily remembered for being instrumental in setting up the supply of free meals for poorer pupils.

A specially interesting and well-organised system of food supply is that of the East Lambeth Teachers’ Association, which in the winter of 1902-03 provided nearly 93,000 dinners for the needy children of 38 South London schools. The Fund, which has been in existence since 1892, originated in this wise: Mr W. H. Libby, the headmaster of the Board School at Victory Place, Walworth, noticing two brothers in his school who seemed very weak and languid, asked if they were hungry. “Yes, sir,” was the answer, “we have had nothing to eat for two days.” To test the truth of this statement Mr Libby sent out for a pennyworth of the stalest bread that could be obtained; this he gave to the boys, and they devoured it ravenously. Believing this to be no isolated case, though perhaps a specially bad one, Mr Libby enlisted the sympathy and help of his fellow-teachers, and the Scholars’ Free Meal Fund was started.

Very substantial help was obtained from a gentleman whose ambition it was to convert the world to vegetarianism, and in deference to his views the Association still works on strictly vegetarian lines. The dinners consist of soup or pudding, and the preparation and distribution are carried out in a quite unique manner. The crypt of St Peter’s Church, Walworth, has been equipped as a food supply depot, and is under the management of the Rev. Canon Horsley, M.A., and an energetic band of voluntary workers. Here the food for all the participating schools is cooked overnight, and placed in specially made asbestos-lined vessels, in which it will keep hot for twenty-four hours. In the morning the cans containing the hot soup or pudding, as the case may be, are despatched by vans to reach the different centres in time for dinner. If required, the Association can supply 5000 meals a day at an inclusive cost of a penny per meal.

One admirable feature about the Lambeth system, which might with advantage be widely extended, is that meals are provided not only for destitute children but for those who are able and willing to pay the cost of the meal. Thousands of Board School children are unable to get a comfortable and nourishing meal at home because their mothers are obliged to go out to work. Such children are sent to school with a make-shift dinner, consisting probably of slices of bread and butter, or with a few pence, which they expend not more wisely than might be expected. In winter time a hot dinner obtainable at school for a penny or twopence would be a real boon to many such, and not the least advantage of the extension of this system would be that no stigma of pauperism would attach to the eating of a school dinner. At the Lambeth schools the diners do not know who of their number have paid the full price, who part of the cost, and who have come in with free tickets. [25]

By the time I was a pupil at the school, every school in the country offered cooked school dinners as a matter of course. At Victory Primary School these were prepared on site, and were available to each pupil, if desired, for one shilling a day. Each dinner consisted of a meat dish (e.g., shepherd’s pie, roast beef, sausages, toad in the hole, etc.) plus potatoes and “greens”; and this main course was followed by a dessert—pudding and custard. The alternative was to go home for dinner, but few did.

In addition, at morning break, each child was given free a small bottle of milk (one third of a pint). The welfare state truly catered for the welfare of its children.

Questions in Parliament

We next hear of the school in August 1909 when a question is raised in Parliament regarding the adequacy of its facilities. By this time the London School Board had been abolished by the Education Act of 1902, and its responsibilities for education in London had passed to the London County Council (formed in 1889). [26]

Mr. Ramsay Macdonald asked the President of the Board of Education [i.e., Department of Education] whether he has received a memorandum from the managers of the Victory Place Schools, Walworth, stating that the schools are so badly lit as to cause injury to the children’s eyesight, that the sanitary arrangements are insufficient, that they are inefficiently equipped in case of fire, and showing that these complaints are supported by His Majesty’s inspectors; whether the memorandum draws his attention to the delay on the part of the late School Board and the London County Council in remedying these defects; and whether the Education Department proposes to compel the education authority to take immediate action regarding this school?

To which Mr. Runciman, the President of the Board of Education responded:

I have received a memorandum from the managers of this school, which includes the criticisms to which the hon. Member refers. The condition of the premises has been adversely reported upon by His Majesty’s inspector, and the Board have already been in communication with the London County Council on the subject. The managers’ memorandum will now be referred to the Council for their observations. [27]

These criticisms are surprising given the very positive appraisal of the new school buildings in the periodical The Architect cited above, especially the complaint that the sanitary arrangements are insufficient. In The Architect we were told that: “Especial attention has been paid throughout to the sanitary arrangements.”

I have yet to discover what immediate actions, if any, were taken by the London County Council in response to the complaints cited by Ramsay Macdonald, but a few years later, the original school buildings were demolished and the current school building was erected. This does not seem to have been a direct response to the complaints described above, although they may have been a factor in the decision-making process.

The Rebuilding of the School—Dates

According to what seems to be an authoritative source—the London Metropolitan Archives—the demolition of the old school buildings and the erection of the new took place in 1913-14. [28] However there is reason to think that these dates may be inaccurate, and should be 1912-13 or 1912-14.

The evidence for a 1912 start is the fact that the District Surveyor summonsed the builders Holliday & Greenwood for failing, on or before 6 September 1912, to serve a building notice on him with regard to Victory Place School as required by the London Building Act of 1894. [29] (On appeal, the builder and the LCC were vindicated.) [30] This suggests that work began on replacing the school buildings in September 1912, since only two days notice was required. [31]

An earlier start date than 1913 is also indicated by the fact that in late July 1913, the Education Committee reported to a meeting of the London County Council that the new building was “nearing completion, and would shortly be ready for occupation”. [32]

Also, in The Times of 12 March 1913 there is a call for tenders for the “installation at the Victory-place Elementary School, Walworth” of “about 178 lighting points”. [33] This suggests that building progress was at an advanced stage earlier in the year.

If the new building was “nearing completion, and would shortly be ready for occupation” in late July 1913, then it is likely that it was completed before the year was out, and perhaps in time for the beginning of the 1913-1914 school year.

The Annual Report of the Council, 1914, states that the rebuilding of Victory Place School “was completed during the year”,[34] but If the Report covers the year from April 1913 to March 1914, as the alternative title given by Google indicates (“Annual Report of the Proceedings of the Council for the Year Ended 31st March 1914”), then it is possible that what is referred to here is completion in 1913 rather than 1914. [I am forced to resort to conjecture here because of the restrictions imposed by Google’s “snippet view”.]

The Rebuilding of the School—Reasons

The rebuilding of the Victory Place school was not an isolated instance. Many Board school buildings were rebuilt as a result of government-imposed requirements introduced from 1907.

Some rebuilding of the first crop of SBL [School Board for London] schools from the 1870s was found necessary by the LCC [London County Council]. The problem was not their condition—the demolished schools were substantial structures with an average age of only 50 years—but an obsolescence caused by changes in planning and accommodation standards. In 1907, the Board of Education established new building regulations for elementary schools, including ‘certain requirements as to plans’, standardised classroom sizes and the provision of halls, gymnasia and playgrounds. In 1912, the LCC introduced the so-called ‘40 and 48’ scheme with the approval of Board, which set class size maxima of 48 for infants and 40 for senior pupils, requiring 120,000 additional places, spurring a capital investment programme which only saw completion in the mid-1930s. It was not due to their age, quality or condition that many board schools were rebuilt. Indeed, their very permanence made them inflexible buildings and in some cases remodelling was deemed prohibitively difficult, making demolition the only apparent answer.[35]

In order to spur it on to greater efforts and to encourage more rapid improvements, the Board of Education was not averse to withholding funds from the London County Council. For example, in November 1910 the Board of Education is reported to have withheld £65,967 because the classes in the London County Council’s schools contained more than 60 pupils each. The Council responded with a statement that it had “for a long time been hurrying forward the erection of buildings in order to allow of more classes being arranged”.[36]

Since the Board of Education had made it clear that the maximum of 60 per class was only a temporary measure, and that it intended to further reduce the number allowed in a class from time to time, the London County Council decided in 1912 to embark upon the “40 and 48” scheme, i.e., to restrict classes to a maximum of 48 in the infants and 40 at the junior levels.

Cyril S. Cobb, a leading member of the London County Council from 1905, and chairman from 1913 to 1914, explained the rationale for this as follows:

Now our experience has shown us that the difficulties of the London area render it extremely inconvenient—indeed, wellnigh impossible—for us to deal from time to time with successive reductions of this kind. It is much better, and far more economical, for us to deal with the whole question at once... [37]

In any case the London County Council had already adopted the maximums of 40 and 48 for all new buildings back in 1907.[38] Now it intended to adapt or rebuild older schools to these new requirements. Thus in 1912 a programme of enlargement, structural improvement or rebuilding of existing schools was embarked upon. At this point the fate of the 1875 Victory Place school buildings was sealed.[39] They would be demolished and replaced by one new three storey building.

The New Building

The new school building was probably designed by Robert Robertson who from 1911 was the Chief Divisional Architect (Schools) in the London County Council Architects’ Department, but this needs to be confirmed through further research. The new building is described by one researcher, Tim Walder, as follows:

The current building is a good example of how the LCC moved on a little following Bailey’s death. It is a three storey single block without wings in yellow London stock brick with minimal ornamentation but with the vestiges of a Queen Anne feel. It does not yet have the eaves or more complex roof outline of the later LCC Philip Webb style schools. The effect is plain but massive and quite strong. [40]

View of Victory Primary School from the entrance to Elba Place looking South East, 2002. (Photo: Pavlos Andronikos)

To my mind, the school’s classical simplicity is both elegant and functional. As a former pupil (1958-1964) I can testify that even as a boy I was fond of the school building. From the point of view of a young pupil, it was roomy, bright, airy, and reassuringly solid.

View of the rear and north side of Victory Primary School from Elba Place, 2002. (Photo: Pavlos Andronikos)

“The Caretaker’s House”

One small building in the North West corner of the site was saved from demolition when the 1875 buildings were torn down. When I was a pupil at the school it was called “the caretaker’s house”, and the caretaker did indeed live there, but that may not have been its original function since, as we saw above in the extract from The Architect, the ground-floor of the main building included “the caretaker’s apartments”. Perhaps the house was accommodation for the Head Teacher.

The “caretaker’s house”, Oct. 2016, from the entrance to Elba Place. (Photo: Google Maps Street View)

Charlie Drake (1925-2006)

The comedian and actor Charlie Drake (professional name of Charles Edward Springall) attended Victory Place school in the 1930s. He then went on to Paragon Row senior school, which he left at the age of fourteen. Drake was his mother’s maiden name.

Interestingly a girl with the surname Drake is mentioned in an 1897 edition of The Academy magazine in relation to a competition in Walworth schools to write an esssay on Robert Browning. Perhaps the Drake family were long time Walworth residents.

“’God’s in His heaven, all’s right with the world,’ sang the poor mill-girl, and Browning truly believed this to the end of his life,” writes Nita Laurie Drake, also of Victory–place School, Standard VII; and she adds: “It was while walking through the fields and leafy lanes of Dulwich that many of his best ideas came into his mind.” [41]

“Destroyed in the War”?

In my researches I came across a reference to the school’s being “destroyed in the war”, but I have been unable to confirm the statement:

... In 1933, he [Francis Llewelyn Powys] married Sally Upfield, daughter of the Headmaster of Victory Place School, Walworth—one of the schools destroyed in the war.[42]

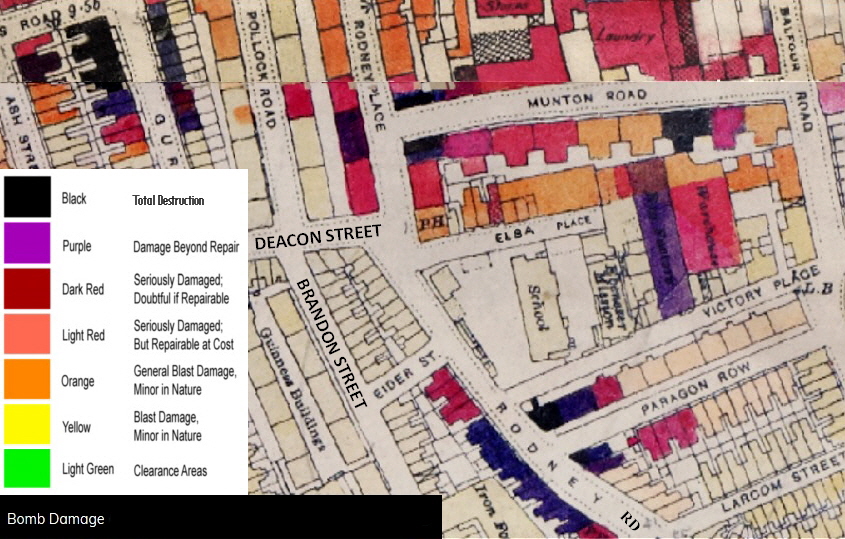

As far as I can discover no bombs fell on the school, neither in the 1st, nor in the 2nd World War.[43] However, some bombs fell very close to the school in the 2nd World War.

Recently, in 2015, Laurence Ward, a curator at the London Metropolitan Archives, published a book of the London County Council’s Bomb Damage Maps, which are hand-coloured to show the extent of the damage inflicted on London by the Luftwaffe.[44] The map showing the school and the surrounding area confirms that the school was not damaged by bombs. However, the southern end of the Palatinate Building on Rodney Place was badly damaged, as were the buildings on the other side of Rodney Place in Munton Road. Curiously, the damage shown in the map on the south west side of Rodney Road does not agree with what I remember. As I recall, the rectangle formed by the streets Deacon, Eider, Brandon and Rodney Road was uneven waste ground which everybody called “the bomb site”, and this waste ground extended across Eider Street. The row of buildings on Rodney Road was clearly missing one or two buildings at the Eider Street end for one could see on the side of the first building the remains of living rooms. (A correspondent, Bill Giddings, who lived in nearby Dawes House during the War, informs me that the site was “cleared after the War for redevelopment”. He also informs me that a little further along Rodney Road, opposite Paragon Row, he recalls “the line of ack ack [anti-aircraft] guns during the Blitz … manned by the ATS girls.”)

On a personal note, it is fascinating to see that my family home in the late 50s and early 60s, 3 Elba Place, is coloured dark red!

A New Name

The Victory Place School was renamed Victory Primary School in 1951. Presumably this was because calling it Victory Place School no longer made as much sense since the main entrances to the school were now on the northern side in the cul-de-sac Elba Place. Another motivation may have been the desire to imply that the victory referred to in the name was the triumph of the allies in the 2nd World War, as well as Nelson’s flagship H.M.S. Victory, and the defeat of Napoleon, commemorated by the street name Victory Place.

Thank You Film Award

In 2014 Victory Primary School won the national Thank You Film Awards competition (London Primary School section) with the film “Today I Will Sing For You (Daddy Song)”. The competition was organised by the Jubilee Centre for Character and Virtues of the University of Birmingham.[45] The award-winning video was produced and directed by Zuzana Pelaez, and was filmed by the “Reception Class children and their dads”. It features a very appealing song and music by Alejandro Pelaez.

Most of the action takes place in what used to be the Girls’ Playground (Western Playground). The façade of the school building can frequently be seen. Also visible is the “the caretaker’s house”.

Pavlos Andronikos

December 2016, August 2020

This postscript/appendix is most of a letter I received from one of the readers of this article, James Hart. Not only was he a pupil at the school, but also, from 1946 when his father was appointed caretaker, he lived in the school grounds. I include the letter here with his permission.

Dear Pavlos,

My mum was evacuated to Cornwall in 1941 and I was born on 20th May that year. We moved back to the family home in Ripley Street, the other side of the New Kent Road, later that year.

When my dad was demobbed from the British Army in 1945 he managed to get employment as an assistant caretaker at the Borthwick [Training] College for Women in London. However in 1946 he applied for employment with the London County Council, and was offered the position of school keeper at Victory Place, which he accepted. We moved in to the school house that same year.

During the war the school was commissioned by the London Fire Brigade/Auxiliary Fire Service and taken over as a fire station. Remarkably, considering the damage in the adjoining and nearby streets, the school did not take any bomb damage during the 1940/1941 Blitz of London. However, there was much work to do. One strange feature of the occupation of the school by the Fire Services was that they kept pigs in the school playground, proper brick-built sties which, of course, had to be removed before school could reopen. There was much to be done inside the school building as well. My dad’s pride and joy were the three halls [one on each floor] with the lovely woodblock flooring. He took great delight in waxing and polishing them during each term break.

Heating the school was a huge job. In the back playground there was a boiler room with three very large boilers which had to be kept well stoked to keep staff and pupils comfortable during the nasty winters we had then.

Evening Classes for a variety of subjects were later introduced. It was a full on job.

We were so lucky to have a nice detached house—a fantastic feature being open fires in each of the three bedrooms. There was also a bathroom—a far cry from the washing facilities and outside toilet we had in Ripley Street. The ground floor was a large kitchen where, on the school’s reopening, lunchtime meals were prepared and cooked for the pupils and staff. The kitchens were also used for cookery lessons as an Evening Class. Later the preparing and cooking of meals was stopped and ready prepared and cooked meals were delivered daily.

I started at the school on its reopening in 1947. It was magic to just walk out of our backdoor and into the playground, and home for lunch every day. I left the school in 1952 as Head Boy, with a grammar school education beckoning. I was accepted at Alleyn’s School in Dulwich. I was very relieved at this as my second choice was St. Olave’s, which I only realised was a rugby-playing school after nominating it!

Living in the schoolhouse it was natural that Elba Place would be one of my main playing areas, apart from the bomb sites nearby. It was a big surprise to see you lived in Elba Place. A number of my friends lived there. We frequented the Archduke Charles where the landlord would let us sit all evening with a pint of mild and playing darts. There was Mickey and Jerry Hubble at number 1; Norman, Kenny and Ernie Robinson at number 2; Eddie, Ena and Bert Hughes, and Ronnie Osborn at number 3; and finally, Rosemary Davison, whose family owned the woodyard at the end of the street. I wonder if any of those family names are familiar to you. We were also weekly attendants at the Ebenezer Mission where, for 1d [one penny], we could get a slice of bread and jam and a glass of hot orange squash.

We eventually moved from Victory Place in 1960 to a school in Eltham.

On leaving school I had a couple of jobs before being made redundant and offered a position in Norway by one of the companies responsible for making me redundant. We spent four years there from 1969 to 1973 and both our children were born there. I’m still married to Pauline after 59 years and we now live in … Kent.

[….]

It was lovely to come across a former Elba place resident. They were happy days.

In closing may I say I am in awe of the work, effort, dedication and research you must have undertaken to write the short history of Victory Place. I’m very glad I found it.

Take care and stay well.

Best regards,

Jim Hart

2 March 2021

[1] See Hansard House of Lords Debate, 25 July 1870, vol. 203, cc. 821-65 at http://hansard.millbanksystems.com/lords/1870/jul/25/elementary-education-bill#s3v0203p0_18700725_hol_21.

[2] Donald James Mackay Reay, Final Report of the School Board for London, 1870-1904 (P. S. King & Son, 1904), pp. 11-12. Available at https://archive.org/details/finalreportscho00reaygoog

[3] “In 1873, twenty-eight schools were provided, with accommodation for 22,218 children. In 1874, seventy new schools were provided, with accommodation for 64,961 children; and, by the end of 1875, a total of ninety-nine new schools had been provided, with accommodation for 88,913 children.” (From Donald James Mackay Reay, Final Report of the School Board for London, 1870-1904 [P. S. King & Son, 1904], p. 12. Available at https://archive.org/details/finalreportscho00reaygoog .)

[4] “Opening of a Board School”, The Times, 25 Nov. 1874, p. 5.

[5] Edward Walford, “Newington and Walworth”, in Old and New London, Volume 6. (London: Cassell, Petter & Galpin, 1878). Available at http://www.british-history.ac.uk/old-new-london/vol6/pp255-268.

[6] See http://maps.southwark.gov.uk/connect/southwark.jsp?mapcfg=Historical_Selection&tooltip=Hist_tips 1936-1952 map.

[7] John Timbs, Curiosities of London, 1867, quoted at http://www.victorianlondon.org/health/lockhospital.htm.

[8] “London”, a map compiled and engraved by Edward Weller; revised and corrected by John Dower, 1866; updated by G. W. Bacon to 1868 (London: G.W. Bacon & Co., 1868). Available at http://london1868.com/.

[9] Possibly this is the ragged school referred to by Michael Collins in The Likes Of Us: A Biography Of The White Working Class (Granta Books, 2014), chapter 2, when he writes: “A ragged school in Walworth was started in a loft over a disused cowshed.” (https://books.google.com.au/books?id=aVW5BAAAQBAJ)

[10] Minutes of Proceedings of the School Board for London, Volume III, 4th December, 1872, to 26th November, 1873 (London: Yates & Alexander, n.d.) available at https://books.google.com.au/books?id=WSw4AQAAMAAJ; and Minutes of Proceedings of the School Board for London, Volume IV, 10th December, 1873, to 25th November, 1874 (London: Yates & Alexander, n.d.) available at https://books.google.com.au/books?id=zik4AQAAMAAJ.

[11] “Eighteen months ago new schools … were opened, in connexion with St. John’s Church, York Street, Walworth, capable of affording accommodation for 600 children.” From “St. John’s, Lock’s-Fields, Walworth” in The Charities’ Record and Philanthropic Messenger 30 Sept. 1867, p. 32.

[12] Minutes of Proceedings of the School Board for London, Volume III, 4th December, 1872, to 26th November, 1873 (London: Yates & Alexander, n.d.) p. 77.

[13] Minutes of Proceedings of the School Board for London, Volume III, 4th December, 1872, to 26th November, 1873 (London: Yates & Alexander, n.d.) p. 122.

[14] Minutes of Proceedings of the School Board for London, Volume III, 4th December, 1872, to 26th November, 1873 (London: Yates & Alexander, n.d.) pp. 139 & 187.

[15] Minutes of Proceedings of the School Board for London, Volume III, 4th December, 1872, to 26th November, 1873 (London: Yates & Alexander, n.d.) p. 200.

[16]

Minutes of Proceedings of the School Board for London, Volume III, 4th December, 1872, to 26th November, 1873 (London: Yates & Alexander, n.d.)

p. 137, 139 & passim.

In the Lambeth Archives there is a copy of a conditional

agreement for purchase by the School Board for London of the land on which Victory Place School

was built. The agreement is dated 26 May 1873.

See

http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/rd/e663c9f1-bb8f-4c29-a848-aaf12c9546ab.

[17] Minutes of Proceedings of the School Board for London, Volume III, 4th December, 1872, to 26th November, 1873 (London: Yates & Alexander, n.d.) pp. 825, 827-8, 862.

[18] “Opening of a Board School”, The Times, 25 Nov. 1874, p. 5. See also The Building News & Engineering Journal, Friday 27 November 1874, vol. 27, p. 651.

[19] Minutes of Proceedings of the School Board for London, Volume III, 4th December, 1872, to 26th November, 1873 (London: Yates & Alexander, n.d.) pp. 664, 672, 911.

[20] See Edward Robert Robson, School Architecture: Being Practical Remarks on the Planning, Designing, Building, and Furnishing of School-Houses (London: J. Murray, 1874), 486 pages. Available at https://archive.org/details/schoolarchitectu00robsuoft

[21]

“New Buildings and Restorations: Rodney Road Board Schools, Walworth”,

The Architect, p. 312 (5 Dec. 1874). Available at

https://books.google.com.au/books?id=r1k_AQAAMAAJ

.

See also The British Architect, 4 Dec. 1874, p. 353 column A. Available at https://books.google.com.au/books?id=VqoQAQAAMAAJ).

[22] Ordinance Survey Map of London, Sheet XI 5, revised 1893, published 1895. Available at http://maps.nls.uk/view/101202171.

[23] Cinema Studies, volumes 1-2, 1960, p. 19 ( https://books.google.com.au/books?id=TVVXAAAAIAAJ).

[24] “The Power of Love” in The Manchester Guardian, 27 Mar. 1950, p. 5 (http://pqasb.pqarchiver.com/guardian/doc/479016030.html ).

[25]

Hugh B. Philpott, London at School: The Story of the School Board, 1870-1904

(London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1904) pp. 294-295. Available at

https://archive.org/details/londonatschoolst00philiala

See also

http://hansard.millbanksystems.com/commons/1905/mar/22/civil-services#column_871.

[26] The final meeting of the London School Board was held in April 1904. See “London School Board: The Final Meeting”, The Times, 29 April 1904, p. 7. Also “London School Board”, The Times, 29 Apr. 1904, p. 12. (The Times Digital Archive. Web. 3 Oct. 2016.)

[27] Hansard House of Commons Debate, 30 August 1909, vol. 10, c5. See http://hansard.millbanksystems.com/commons/1909/aug/30/victory-place-schools-walworth#column_5

[28] Go to London Metropolitan Archives and search for “Victory Place School”, then click on the word “Series” in the result which has the reference code LCC/EO/DIV08/VIC.

[29] The Justice of the Peace Reports, vol. 78, 18 July 1914, p. 262 (https://books.google.com.au/books?id=dTlAAQAAMAAJ).

[30] The Building News: No. 3096, 8 May 1914, p. 633 in The Building News and Engineering Journal, vol. 106, January-June, 1914 (https://www.myheritage.com/research/record-90100-33439644/the-building-news-and-engineering-journal-vol-106-january-june#fullscreen).

[31] The London Building Act, 1894, Article 145 (https://archive.org/stream/londonbuildingac00fletrich#page/112/mode/2up).

[32] The Building News: No. 3056, 1 Aug. 1913, p. 140 in The Building News and Engineering Journal, vol. 105, July-December 1913 (https://www.myheritage.com/research/record-90100-33426149/the-building-news-and-engineering-journal-vol-105-july-december#fullscreen).

[33] “The Times Engineering Contract List.” The Times [London, England] 12 Mar. 1913: 26. (The Times Digital Archive. Web. 21 Sept. 2016.)

[34] Annual Report of the Council, 1914 (London County Council, 1914), vol. 1, p. 212 (https://books.google.com.au/books?id=FRctAQAAMAAJ).

[35] Geraint Franklin, Inner–London Schools 1918–44: A Thematic Study (Research Department Report Series No. 43-2009. ISSN 1749-8775) © English Heritage 2009, page 24. Available at http://services.english-heritage.org.uk/researchreportspdfs/043_2009web.pdf

[36] “Education in London”, The West Australian (Perth, W.A.) 29 Nov. 1910, page 5 (http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/26297230).

[37] Cyril S. Cobb, London Education: Lecture at Caxton Hall, 6 June 1912. See https://books.google.com.au/books?id=5QPiAAAAMAAJ.

[38] Cyril S. Cobb, London Education: Lecture at Caxton Hall, 6 June 1912. See https://books.google.com.au/books?id=5QPiAAAAMAAJ.

[39] London Municipal Notes, Volume 15 (London Municipal Society, 1912) p. 115. See https://books.google.com.au/books?id=xRgZAAAAYAAJ

[40] Source: http://www.victorianschoolslondon.org.uk/Schools.htmx?schoolid=584. The LCC’s school-building programme was initially run from the education department by T. J. Bailey, formerly Architect to the School Board for London. He retired in 1910.

[41] “Some Child-Critics of Browning: A Board School Experiment” in The Academy vol. 51, 29 May 1897, pp. 573-4. For biographical details see Lawrence Goldman (ed.), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography 2005-2008 (Oxford: O.U.P., 2013), p. 328 (https://books.google.com.au/books?id=nbGcAQAAQBAJ). See also “Charlie Drake, Obituary” by Stephen Dixon in The Guardian 28 Dec. 2006 at https://www.theguardian.com/media/2006/dec/28/broadcasting.guardianobituaries.

[42] Oliver Marlow Wilkinson (ed.), The letters of John Cowper Powys to Frances Gregg, Volume 1 (Cecil Woolf, 1994) p. 250. See https://books.google.com.au/books?id=BzZbAAAAMAAJ .

[43] One of the problems in trying to ascertain where bombs fell in the 1st World War is the fact that OCR searches in newspaper archives are of no use because the press was not allowed to report specific details: “The Press are specially reminded that no statement whatever must be published dealing with the places in the neighbourhood of London reached by aircraft, or the course proposed to be taken by them, or any statement or diagram which might indicate the ground or route covered by them.” (From “Detailed Reports Forbidden”, The Times 1 June 1915, p. 8.)

[44] “The Meticulously Hand-Coloured Bomb Damage Maps of London – In Pictures,” The Guardian, Wed. 2 Sept. 2015.

[45] See “Launch of the 2014 Thank You Film Awards” and “Thank You Film Awards London Ceremony 2014”. (Accessed October 2019.) The You Tube video is at https://youtu.be/VOpeOdae1A0.

Warning

Some of the links may no longer be current. An internet search for the title should bring up the current address if

the source is still available.