Mikis Theodorakis, 1925–2021Part 2: Poetry for the Peopleby Pavlos Andronikos, Aug. 2022Published in Antipodes 68, 2022, pp.70-76 |

|

“...who do I write music for? I write for the Greek people.”[1]

One of the primary ways in which the song cycle Epitaphios embodied a musical revolution was in its use of contemporary poetry to create popular songs. With those particular poems by Ritsos that was relatively easy to do because the poems themselves mimic folk song. They use the language and regular metre of folk songs, as well as a traditional and ancient genre of lament, the moirologi (μοιρολόγι), which is still improvised at Greek funerals by female mourners.

The real test was to bring erudite poetry like that of Seferis and Elytis into popular culture through song—poetry which was for the most part obscure in meaning, and which used the irregular forms of free verse.

The opportunity to attempt this presented itself when Theodorakis met the poet George Seferis. In his account of the genesis of the Epiphania [Epiphany] song-cycle, Theodorakis describes how he first met Seferis at the Royal Opera House, London. This was, according to Theodorakis, in the autumn of 1960,[2] when the latter came to the rehearsals for the ballet Antigone for which Theodorakis had written the music. Afterwards they went back to the Greek Embassy near Hyde Park on foot at Seferis’ request:[3]

“The way your music has affected me, I’ll need hours to recover... I’d rather walk.” [4]

In Theodorakis conversations with Seferis it transpired that the poet was thinking along the lines of collaborating in creating a new ballet, but Theodorakis had other ideas:

“How about if I write songs based on your poetry in the meantime?”

“Songs?” [….]

“Next week I will bring from Paris some examples of my work for you to listen to. I’d like to believe that [as a composer] I am not betraying poetry…”

Theodorakis departed from that encounter with a pile of Seferis’ publications to take back with him to Paris, and when he returned to London he brought four new songs and, surprisingly, Hatzidakis’ version of Epitaphios. He was afraid that his own recording might not be well received.

According to Theodorakis, Seferis liked the recording of Epitaphios, but when they were listening to the new songs, which Theodorakis performed at the piano, Seferis’ wife laughed “nervously” [νευρικά]. Theodorakis stopped playing.

“What’s going on, Maro?” Seferis asked sternly.

“Forgive me... But I have heard this poem [Arnisi] recited so many times by George, that it seems really strange to me to hear it with music... I like it very much.”

When he had finished singing the four new songs of Epiphania, Theodorakis thought he could discern in Seferis’ eyes “the glow of a creator rejoicing in the new form his poetry was suddenly taking.”[5] However, we have testimony from Seferis himself which indicates that he was not entirely happy with the fruits of Theodorakis’ labours:

I didn’t much like it; maybe that’s the fault of freezing London. ‘Denial’ [Arnisi] seems better than the rest which seem to me a bit garbled, missing the meaning. But even in ‘Denial’, the lack of a pause before the word ‘wrong’ makes nonsense of the last verse. Unfortunately, Th[eodorakis] thinks he knows everything . . . forgive me, my dear George [Savvidis], but I’ve a different idea of the craftsman.[6]

It is possible that Seferis changed his mind when he saw how popular Arnisi [Denial] became. Theodorakis describes with satisfaction how one night he and Seferis, along with George Savvidis and the younger George Papandreou, wandered around Plaka from taverna to taverna because Seferis wanted to see and hear the musicians and patrons in all the restaurants singing “By the Secret Seashore” [i.e., Arnisi].

Never perhaps had Seferis become so like a small child. He was laughing, beaming all over with happiness, and I think that that night he allowed his so stern heart to love me. To the extent, of course, permissible for a diplomat...[7]

For the song-cycle Epiphania Theodorakis had picked only four poems: three from “Notes for a Summer”, the final section of the publication Tetradion Gymnasmaton [Book of Exercises], and one from Seferis’ first published collection Strophe [Turn]. The latter, Arnisi, was relatively easy to set to music. It was comprised of three 4-line verses with a more or less regular metrical pattern and an ABBA rhyme scheme. Seferis abandoned such traditional structures in his subsequent poetry where free verse is the norm.

It was the other three poems which presented the challenge Theodorakis was looking for:

I wanted—precisely because the verse was so intellectualistic—to bring Epiphania to as wide an audience as possible in popular music attire. After all, this was the first time that free verse was aspiring to become simple popular song. That is, to accompany ordinary people everywhere: the building sites, the tavernas, on excursions, at the gathering of friends...[8]

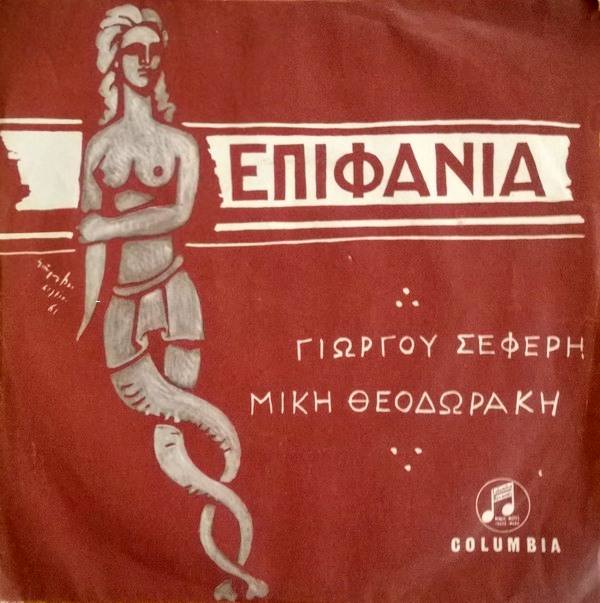

The front cover of Epiphania designed by Bost [Μποστ].

There is no doubt that Theodorakis achieved that kind of popularity with the song Arnisi, which quickly became an extremely popular song and, in time, a widely acknowledged classic, but it is the only song of the four which is not in free verse. Whether the other three songs would have become popular in the same way—the way which Theodorakis wanted—without Arnisi by their side is open to question. The lesson one takes away from the reception of Epiphania is that traditional poetic forms make for more popular songs.

By a strange coincidence it was the Epiphany ceremonies of 1966 which would lead Theodorakis to realise fully his aim of popularising free verse through song. This was achieved with the song cycle Romiosyni.[9]

On 6 January 1966 Theodorakis, now an M.P., found himself at a celebration of the Epiphany in Piraeus. Two rival ceremonies were scheduled but massive crowds had gathered to support George Papandreou, the P.M. who had been dismissed by King Constantine, whereas the King’s ceremony was poorly attended. Furious the police and their thugs attacked the Papandreou crowd. Being very tall, Theodorakis stood out, and he was grabbed, thrown to the ground, and beaten. In one interview he remembers how he was dragged by the feet over the asphalt.[10]

Returning home, he avoided his family because he didn’t want them to see him covered in blood and dirt. He went into the room with the piano to clean himself up, and noticed that somebody had propped Ritsos’ poems for Romiosyni up on the piano. He had had these since 1962 but they had not “spoken” to him. Today, after his experience of police brutality, they did speak to him, and the music poured out of him, by his own account, effortlessly. In a few hours the task was almost completed. He had created eight songs from the free verse of his friend Yiannis Ritsos. The ninth was added later.

In an interview Theodorakis describes how the free structure of the music and the symbolism and imagery posed problems in the performance of the songs. Grigoris Bithikotsis found that the songs did not speak to him, and he felt he couldn’t sing them. Theodorakis recorded himself performing the songs so that Bithikotsis could take the recording home and listen to it there.

I start to listen. Nothing! I listen to it all, go and shave, wash, turn the tape recorder up loud, listen again… Nothing! I couldn’t get into it at any point... One evening, after I had finished at the shop and come home, alone in my room I said to myself, “You have to sing it, Grigori! It’s like the ones before: Epitaphios, Axion Esti and these here. It can’t be—Where’d he get it from? Mars?” … So I lock myself in. “One song!” I say, “Mother of God! One song! If I can learn just one song, I’ll get the sense.” And so I began to sing: “Beneath the soil, in their folded arms they hold the rope of the bell [that will signal the resurrection]…”[11]

Similarly getting the bouzouki players to learn their parts was also a struggle. They didn’t read music so they had to memorize the “irregular” parts for all nine songs. Theodorakis describes in the interview how it took over a month of rehearsals at his place to get the bouzouki and guitar players ready.[12]

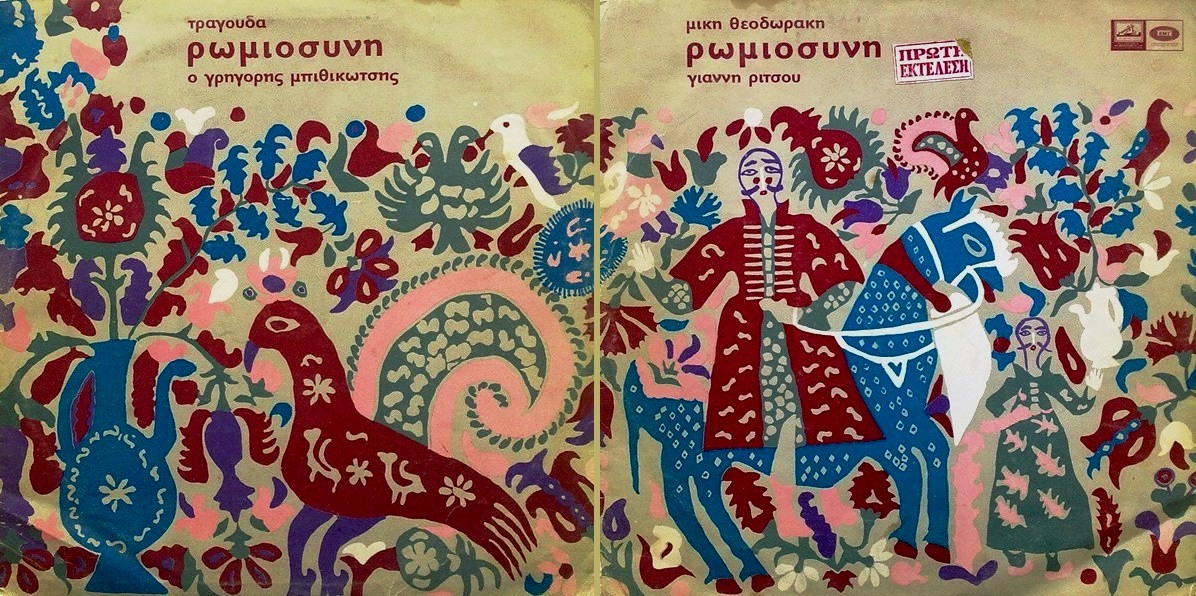

The covers, front and back, of Romiosyni designed by Xanthippi Micha.

When they were ready Romiosyni was presented to enthusiastic audiences all over the country. Given the political nature of the lyrics and the rousing martial character of the songs and music its popularity was assured. These were troubled stormy times, and the songs touched the hearts of their intended audience with messages of resistance and hope. The two most popular (and rousing) songs of the song cycle, both very similar, were/are “When They Squeeze Their Hands [into a fist]” and “The Bells Will Toll”. Both are anthems confidently anticipating a “resurrection”.

Here is how one reviewer, Tasos Vournas, described the massive concert held at the football stadium in New Philadelphia, Athens, on 4 July 1966:

The word “μυσταγωγία”[13] is too cheap and trite to express the public’s deep satisfaction yesterday. It was a national liturgy reminiscent of the great musical outbursts of our People…. Twenty thousand of us drank with our hearts wide open—we drank sound and poetry and couldn’t get enough. And when at the end the verses of Ritsos’ Romiosyni began to fall, one after the other, like hammer blows, brought to us as if they were prayers on the wings of Theodorakis’ music, then we felt in all its intensity the pride of being a Greek fighter devoted to our country, our people and their future. Twenty thousand people, mostly young, the enraged offspring of the Resistance, upright, and with tears in their eyes, cheered and applauded the poet’s verses as they gushed forth with the music like a waterfall…[14]

The reference to liturgy brings me to my last section a brief discussion of…

This work preceded Romiosyni but it does not represent the successful utilisation of free verse in popular song in the way that Romiosyni does. Rather it strives for something new, a combining, or at least a juxtaposing, of classical, popular, and religious musical elements.

Elytis’ text is, in its form and intent, a liturgy, and Theodorakis understood this well, for he clearly regarded his task as being to realise the work as a liturgy, complete with songs, chants, and readings. These were to be performed by a classical orchestra and choir, bouzoukis, a reader, a male soloist, and Bithikotsis.

Despite the classical colour of much of the work, Theodorakis wanted the result to be popular—to be familiar enough to the people so as to speak to them.

I had to find a balance so that this work would not be beyond the sensibility of the people. [Έπρεπε να βρω μια ισορροπία, ώστε το έργο αυτό να μην είναι μακριά από την ευαισθησία του κόσμου.][15]

The first public performance of the work took place on 19 October 1964 at the Rex theatre. Theodorakis and Elytis had wanted the ancient Odeon of Herodes Atticus but the presence of Bithikotsis among the singers was considered by the authorities demeaning to the theatre!

This first performance did not seem to Theodorakis and Elytis to inspire the enthusiastic reactions they had hoped for, and it received mixed reviews, some of them downright petty. However the playwright Dimitris Psathas wrote that the performance was an “excellent musical μυσταγωγία” [that word again] which “captivated and awed the audience”. The response to the recorded version was equally encouraging. It was from the very beginning a massive best seller.

The cover of Axion Esti with the painting which Yannis Tsarouhis created specifically

for the album.

I have to disclose that the Axion Esti is one of my favourite Theodorakis works. Two things in particular stand out for me. The first is the superb readings. Elytis’ prose is exceptional but so too is the voice and diction of Manos Katrakis. Listening to the readings one cannot help but think “What a wonderful and noble language is Greek!” That’s how good the readings are. The second thing which stands out for me is Bithikotsis’ singing. How could anybody regard his singing voice as in any way inferior to classical singing? Think, for example, of those glorious moments in “Με το λύχνο του άστρου” [With the Light of a Star] where his voice cuts in with that wonderful line “πού να βρω την ψυχή μου…” [where will I find my soul]. Amplified in expression and feeling by the contrast with the choral voices which precede it, Bithikotsis’ voice soars! Without him Axion Esti would be a much lesser realisation of Theodorakis’ crowning achievement.

There is much else one could say about Mikis Theodorakis. He was a remarkably energetic and prolific composer and activist. However space is limited. I will use what little is left to reveal that, as a composer myself, I intentionally incorporated an allusion to Theodorakis in the introduction to my setting to music of the poem by Michael Pais “With the Lips of Heartache”.[16] It was intended as an acknowledgment of my own debt to him. I have been listening to his songs since I was a child, and they have become a very significant part of my cultural world. I will let him have the last word:

“I lived my life well. What I wanted to do I did. From here on, I am handing the baton over to you...”[17]

* * * * *

Mikis Theodorakis in the ERT documentary Τραγούδια που έγραψαν ιστορία: Ρωμιοσύνη. Directed by George Zervas. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fARYsW-S1qM) All translations of quotations are by me unless otherwise stated.

See Mikis Theodorakis, Μελοποιημένη ποίηση, vol. 1 (Ύψιλον, 1997) p. 54. No performance is listed for Autumn 1960 on the Royal Opera House Performance Database, but there

was a performance on 11 October 1961 with the conductor John Lanchbery.

(See

https://www.rohcollections.org.uk/Production.aspx?production=4322.)

Either the Database has not listed all performances or Theodorakis is mistaken as to the year.

This cannot have been Theodorakis’ first meeting with Seferis. The latter mentions attending a

concert in Athens on 25 August 1960 to hear the Firebird by Stravinsky and a suite by Theodorakis.

Afterwards he had dinner at a taverna with a group which included Theodorakis and Theodorakis’

father. There is no mention here by Seferis of a meeting with Theodorakis in London in the autumn

of that year. (Μέρες Ζ’, 1 Οκτώβρη 1956—27 Δεκέμβρη 1960, edited by Theano Michaelidou [Athens: Ίκαρος, 1991] p. 241.)

I would like to take this opportunity to acknowledge the advice and suggestions of Theano Michaelidou.

We were students together at Birmingham University, and she has been my dear friend and sounding board

in Greece for many years.

George Seferis was the Ambassador of Greece to the UK at the time.

Quoted in “Μίκης - Σεφέρης: «Προσοχή στην άνω τελεία»” by Angela Kotti (Πολιτισμός 2 Sept. 2021). This reference also applies to the two quotes below.

Ibidem.

From a letter to George Savvidis, 19 January 1962, quoted in translation by Roderick Beaton in George Seferis: Waiting for the Angel: A Biography (New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 2003) p. 362.

Quoted in “Μίκης - Σεφέρης: «Προσοχή στην άνω τελεία»” by Angela Kotti (Πολιτισμός 2 Sept. 2021).

From https://www.mikistheodorakis.gr/el/music/ergography/beforedictatorship/?nid=4689.

Note the word Theodorakis uses here: “διανοουμενίστικος” which I have rendered “intellectualistic”.

The term Romiosyni is untranslatable. Its root is the name “Rome” and it refers to the Eastern Roman Empire [mistakenly called Byzantine in English] and its world. In modern Greek it refers to Greece and the Greek world.

The ERT documentary Τραγούδια που έγραψαν ιστορία: Ρωμιοσύνη. Directed by George Zervas. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fARYsW-S1qM)

Ibidem.

Ibidem.

The word “μυσταγωγία” could mean an initiation into sacred mysteries, the mysteries themselves; or the ecstasy experienced by the spectator/listener of an exceptional musical or theatrical work. It could also refer to a work which has the power to evoke such an experience.

«Ακούγοντας τη μουσική του Μίκη Θεοδωράκη», Tasos Vournas, Avgi 6 July 1966, p. 2. See https://anazitisinews.gr/2021/09/03/cc/.

Quoted in “Άξιον Εστί: Η μνημειώδης συνεργασία Μίκη Θεοδωράκη και Οδυσσέα Ελύτη” by Yiannis Diamantis in Ta Nea (Greece) 2 Sept. 2021.

“With the Lips of Heartache” can be heard here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xSlSaSW5fNE.

«Εγώ έζησα ωραία την ζωή μου. Εκείνο που ήθελα να κάνω το έκανα. Από εδώ και πέρα σας παραδίδω τη σκυτάλη…» From the ERT documentary Τραγούδια που έγραψαν ιστορία: Ρωμιοσύνη. Directed by George Zervas. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fARYsW-S1qM).