Mikis Theodorakis, 1925–2021Part 1: The Musical Revolutionby Pavlos Andronikos, Oct. 2021Published in Antipodes 67, pp. 88-93 (Melbourne: G.A.C.L., Dec. 2021) |

|

The recent death of Mikis Theodorakis is not cause for grief. He lived a long and fulfilled life, and left behind him much wonderful music—a gift to Greece and the world. However it is sad that relatively few non-Greeks have even an inkling of how great a composer he was. Most people know him only through “Zorba’s Dance” and his music for the film Zorba the Greek.

“… the negative aspect is that now, as far as the great masses are concerned, a stamp of identification has been placed upon me. I am Zorba's music. Even Fidel Castro—the only music he has on his boat when he goes on an excursion is Zorba; and he knows me as Zorba.” (Mikis Theodorakis, translated) [1]

This limited awareness is a great shame. “Zorba’s Dance” is excellent indeed, particularly the original recording, and fully deserving of its fame, but it is not an isolated instance. Theodorakis was one of the greatest and most prolific songwriters and composers of the twentieth century, and deserves a reputation equal to that of, for example, Bob Dylan. Certainly he looms just as large in the Greek world as Dylan does in the English-speaking world.

Theodorakis’ music first rose to prominence in Greece in 1960 when he started a musical revolution by creating a new sound and a new genre of song—the έντεχνο λαϊκό [artistic popular song]. This revolution was heralded by and embodied in the song cycle Epitaphios, a work which still stands, alongside so many others, at the pinnacle of Theodorakis’ achievement. Its importance as a pioneering work cannot be overstressed.

Those of us who lived through the 60s know from that experience that, in music, the coming together of particular individuals can generate the most sublime magic. Talent alone is not enough. Fortune must first bring together the specific mix of musicians which the magic requires. The greatest example of this was, of course, the Beatles, but also the Rolling Stones.

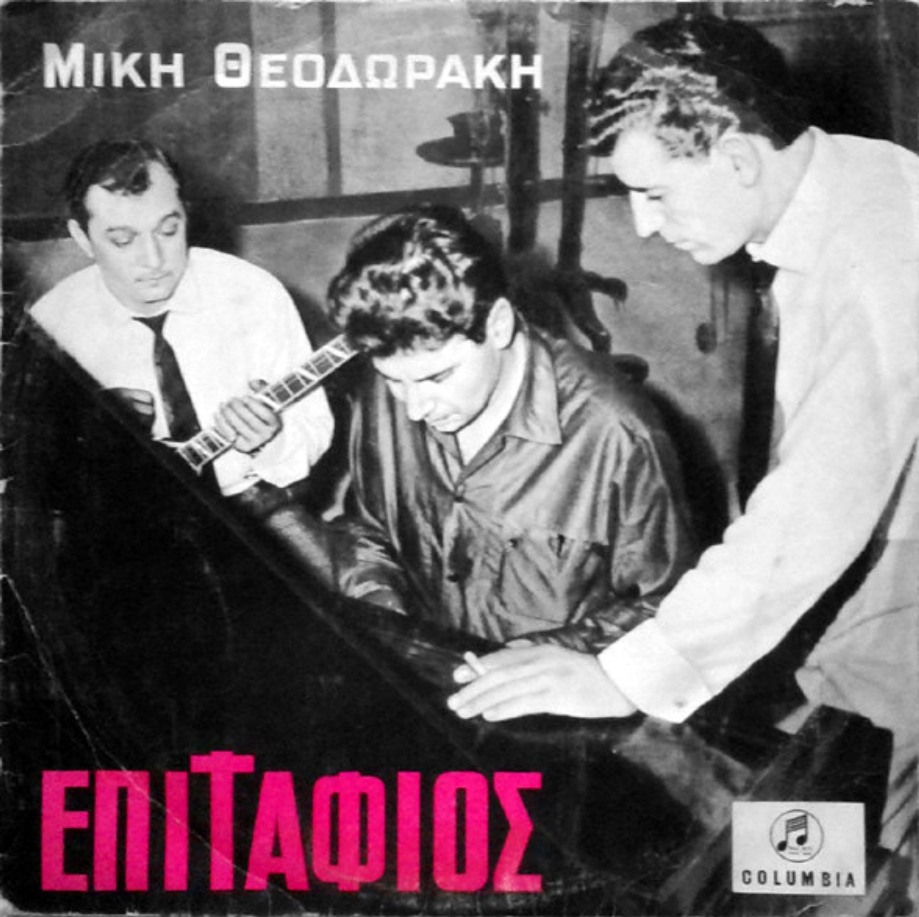

In the case of Theodorakis it was the Epitaphios project which contrived the fateful coming together of Theodorakis with Grigoris Bithikotsis, and Manolis Chiotis. That trio was the essential combination from which the musical magic of “κείνες τις γόνιμες μέρες“ [those fruitful days] stemmed. [2]

It is interesting to note that the formation of the trio was not a foregone conclusion. A series of twists of fate was required. Without them the history of Greek popular music might have been quite different.

The story begins in 1957 with the poet Yiannis Ritsos sending a copy of the second edition of his small collection of poems Epitaphios to Theodorakis in France, where he was studying classical music at the Conservatoire de Paris. [3] Theodorakis selected eight of the twenty poems in the booklet and set them to music, which he then sent to Manos Hatzidakis (in 1958), but nothing came of that initiative. [4]

In mid-1960 Theodorakis was back in Greece for the staging of The Phoenician Women at Epidauros by the National Theatre using his music. With that job done, he was getting ready to return to France with his family and continue his classical music career when a reunion with a friend from his EPON days, Dimitris Despotidis, set him on a different path.

At Despotidis’ request, the two went to see Manos Hatzidakis (also formerly of EPON) to ask him to speak to Prime Minister Konstantinos Karamanlis about the plight of left-wing political prisoners. When they raised the subject…

Manos, at that moment, was overcome by meanness, and overreacted. “Listen up now!” He rose from his chair. “I’ve forgotten all that stuff! I have my passport and I can go wherever I want. I like it like that!” (Mikis Theodorakis, translated) [5]

After this disappointing encounter, the two friends reasoned that it was Manos Hatzidakis’ success as a songwriter which gave him access to the mighty, and if Theodorakis could achieve similar success they would not need middlemen. Theodorakis informed his friend that he had a set of songs ready to be recorded called Epitaphios, and he sang some of them to him. Despotidis was impressed by “Μέρα Μαγιού μού μίσεψες” and urged Theodorakis to approach Alekos Patsifas, the head of the Fidelity Record Company. Patsifas agreed to record Epitaphios, and when Theodorakis told him he wanted a laikos vocalist, Patsifas offered Anna Chrysafi.

Nana Mouskouri, who was with the same record company, heard Theodorakis rehearsing with Anna Chrysafi and decided that she wanted to sing Epitaphios herself. But for that to happen Hatzidakis had to give his permission. She was his singer. Hatzidakis agreed on one condition: “Θα καθορίσω εγώ την ορχήστρα.” [“I’ll decide the composition of the orchestra.”] [6] And so the recording of Epitaphios began with Hatzidakis at the helm and Nana at the microphone.

However Fortune had other ideas, and a series of coincidences led Theodorakis to a different record company, Columbia, and to a complete change of plan and personnel.

The coincidences began with Nikos Gatsos the poet being impressed by Myrto, Theodorakis’ wife, and writing a lyric dedicated to her. Theodorakis set it to music, and the song “Μυρτιά” was born.

A little known singer, Giovanna, happened to hear Theodorakis playing the new song to Patsifas, Hatzidakis and Gatsos, and offered her services. They auditioned her, liked what they heard, and recorded her the very next day. [7] The day after that Nana was in the studio working on Epitaphios, and Hatzidakis decided that this was a good time to break the news to her.

… says Manos: “Let's listen to what we recorded yesterday.”

“What did you record yesterday?” Mouskouri pipes up.

“You’ll hear,” Manos replies.

“What are these songs?”

“Some songs that Mikis wrote.”

“When did he write them?”

“Yesterday!”

“And who’s the woman singing them?”

Suddenly Mouskouri was gripped by hysteria, she wanted to break everything around her! There were some enamel ashtrays. Patsifas was giving them to her: “Here, take it, Nana dear,” and she was breaking them one after the other! It could have been a scene from a movie, a great comedy! [8]

Not content with breaking ash trays, Nana later got Patsifas to agree that she would never be asked to sing for Theodorakis again following the completion of Epitaphios. Patsifas’ docile submission to Nana’s will angered Theodorakis, and he abandoned the Hatzidakis recording of Epitaphios and took himself off to the rival record company Columbia. There Fortune granted him Manolis Chiotis on bouzouki.

For a singer, Theodorakis told Columbia that he wanted Grigoris Bithikotsis. They had met once briefly in 1948, when Theodorakis was a political prisoner, and perhaps that meeting was a factor in his desire to have Bithikotsis sing for him:

In 1948 he [Bithikotsis] met Mikis Theodorakis completely by chance in Keratea. There, a truck stopped, which was transporting political prisoners to Lavrion to be ferried to Makronisos. There was a drinking fountain there and one of the soldiers being transferred filled his water bottle and gave the prisoners water to drink. That soldier was Grigoris Bithikotsis. [9]

In 1960 Bithikotsis’ career was not going so well, and he was on the verge of emigrating to Canada to take up his former trade of plumber, but he was found in time, and the trio was complete. There followed fifteen days of rehearsals, after which the whole of Epitaphios was recorded in just two days. The result was thrilling indeed!

For these recordings Bithikotsis sang better than he had ever sung before. He adopted a pure almost classical style: laconic, no slurring, no attempt to overplay the emotion, and yet somehow highly emotive. Logically the songs call for an older female voice, but one forgets this completely listening to Bithikotsis. He becomes the voice of the mother lamenting her murdered son, but also of any person mourning a great loss.

Chiotis played like a man on fire, making the bouzouki a second main voice. The sheer freshness and virtuosity of his playing is irresistible. It is both powerful and delicate; clean, but also full of expression; rich with slides, subtle bends, and rhythmic picking variations. Surely, like Robert Johnson, he must have sold his soul to the devil. His playing is divine.

But divine also is the material he was being asked to play. Theodorakis is unquestionably the master of melody, but in addition he is also the master of memorable instrumental introductions and breaks. These are a characteristic of most of Theodorakis’ songs, but on Epitaphios they come across as an absolutely integral element, an essential part of each song’s appeal. And Chiotis plays them with much verve and, often, when appropriate, with a punchy almost rock sound.

Nowadays purists frown at the use of electromagnetic pick-ups of the kind Chiotis had on his bouzouki. They prefer a clean acoustic sound, and Chiotis has fallen out of favour somewhat. This is foolish. It is akin to wishing that Jimi Hendrix had played guitar without amplification. Chiotis is the acknowledged master of his instrument, and his instrument is the amplified bouzouki. Many of the expressive effects he exploited could not have been achieved on a purely acoustic instrument.

It is said that both Chiotis and Bithikotsis had doubts about what they were creating, but I find that hard to believe. These are not the performances of musicians who do not have faith in what they are doing. They must have loved what they were hearing from the studio monitors or they could not have performed as well as they did. Perhaps the knowledge that elsewhere a rival recording was being made by Hatzidakis, one of the great composers and arrangers of the time, spurred them on. They had to be good, if their version was to stand a chance. Nevertheless all three would have been concerned that the public might not appreciate something as ground-breaking as what they were doing. “Μανώλη, θα ξεφτιλιστούμε,” Bithikotsis is reported to have said. [Manolis, we’re going to be a laughing stock.] [10]

We are used to the sound of early Theodorakis now, and do not realise how “confronting” it was in 1960. When Theodorakis first played the recording of Epitaphios to a gathering of his friends (Hatzidakis, Elytis, Gatsos, and Valaoritis) they burst into laughter before the first track had finished. The only one who liked what she had heard was Hatzidakis’ mother, and she told the assembled company so. Hatzidakis himself assured her that Mikis was pulling their leg. He couldn’t possibly be planning to release what they had just heard. [11] But he was.

In August 1960, Fidelity released Hatzidakis’ recording of Epitaphios, and the following month Columbia released Theodorakis’ version. Many preferred the saccharine sound of Hatzidakis, but over time the Theodorakis/Bithikotsis/Chiotis version became the acknowledged classic. For Theodorakis a great weight was lifted from his soul: the unprecedented success of Epitaphios “created in me a great well-being, an inner peace, a fullness. I would say that I have never been as happy as I was in those years. The acceptance [of my music] by the people was manifest.” [12]

It was much more than acceptance; it was infatuation, it was passionate adoption, it was love.

* * * * *

Part 2 appeared in the 2022 edition of Antipodes.

I was asked to write this article by the current President of the G.A.C.L.M. Cathy Alexopoulos because she wanted to include in the 2021 edition of Antipodes a celebration of the work of Mikis Theodorakis on the occasion of his death. Naturally the task had a word limit and a fast approaching deadline…

* * * * *

* * * * *

Μίκης Θεοδωράκης – Αυτοβιογραφία, Β' Μερος, Γιώργος & Ηρώ Σγουράκη.

Theodorakis’ own description for that period. See https://www.mikistheodorakis.gr/el/music/ergography/beforedictatorship/?nid=4709.

Γιάννης Ρίτσος, Επιτάφιος, 2nd edition (Athens: Kedros, 1956).

A handwritten score can be seen here: https://digital.mmb.org.gr/digma/bitstream/123456789/36699/2/document0b.pdf.

“Τετ α τετ ιστορίες με τον Μίκη Θεοδωράκη: Πώς έγινε ο—κατά Μάνο Χατζιδάκι—Επιτάφιος του με τη Νάνα Μούσχουρη!” (http://bosko-hippydippy.blogspot.com/2017/05/blog-post.html)

Apparently Patsifas was a bit of a scrooge and was constantly trying to save money by limiting the number of musicians used. See Πέπη Ραγκούση, “Αλέκος Πατσιφάς” (25 August 2017) at https://www.tanea.gr/2017/08/25/opinions/alekos-patsifas/.

Giovanna’s recordings were Theodorakis first big hit. A single was released with “Μυρτιά” on one side and “Aν θυμηθείς το όνειρο μου” on the other side. See http://www.45cat.com/record/14008

Αντώνης Μποσκοΐτης, “Ο Μίκης, ο Επιτάφιος, ο Χατζιδάκις, η Μούσχουρη και ο Μπιθικώτσης” (8 Sept. 2021) at https://www.documentonews.gr/article/o-mikis-o-epitafios-o-xatzidakis-i-moysxoyri-kai-o-mpithikotsis/.

“Γρηγόρης Μπιθικώτσης” at https://www.sansimera.gr/biographies/103.

Φώτης Απέργης, “Ο Επιτάφιος που ανέστησε το ελληνικό τραγούδι,” (3 September 2021) at https://www.efsyn.gr/tehnes/moysiki-horos/308738_o-epitafios-poy-anestise-elliniko-tragoydi.

“Μίκης Θεοδωράκης - Επιτάφιος - Η ιστορία των Επιτάφιων - Μούσχουρη εναντίον Μπιθικώτση” at https://youtu.be/S8heJCO72Y8?t=1002.

Μίκης Θεοδωράκης, Πού να βρω την ψυχή μου, τ. 1ος (Εκδόσεις Νέα Σύνορα – Λιβάνης, 2002), σελ. 89.